Jeffrey R. MacDonald

Jeffrey R. MacDonald | |

|---|---|

MacDonald in 1970 | |

| Born | October 12, 1943 Jamaica, Queens, New York, U.S. |

| Occupation | Former physician |

| Spouses |

|

| Children |

|

| Parent(s) | Robert MacDonald Dorothy Perry |

| Motive | Unknown. Possible rage compounded to mimic a Manson-inspired massacre.[1] |

| Conviction(s) | First degree murder (18 U.S.C. § 1111) (1 count) Second degree murder (18 U.S.C. § 1111) (2 counts) |

| Criminal penalty | Life imprisonment |

| Details | |

| Victims | Colette Kathryn Stevenson MacDonald (26) Kimberley Kathryn MacDonald (5) Kristen Jean MacDonald (2) Unborn child |

| Date | February 17, 1970 |

| Location(s) | Fort Bragg, North Carolina, U.S. |

| Imprisoned at | FCI Cumberland, Maryland, U.S. |

Jeffrey Robert MacDonald (born October 12, 1943) is an American former medical doctor and United States Army captain who was convicted in August 1979 of murdering his pregnant wife and two daughters in February 1970 while serving as an Army Special Forces physician.

MacDonald has always proclaimed his innocence of the murders, which he claims were committed by four intruders—three male and one female—who had entered the unlocked rear door of his apartment at Fort Bragg, North Carolina,[2] and attacked him, his wife, and his children with instruments such as knives, clubs and ice picks. Prosecutors and appellate courts have pointed to strong physical evidence attesting to his guilt. He is currently incarcerated at the Federal Correctional Institution in Cumberland, Maryland.

The MacDonald murder case remains one of the most litigated murder cases in American criminal history.[3]

Early life

[edit]Jeffrey MacDonald was born in Jamaica, Queens, New York, the second of three children born to Robert and Dorothy (née Perry) MacDonald. He was raised in a poor household on Long Island,[4] with a disciplinarian father who, although nonviolent towards his wife and children, demanded obedience and achievement from his family. MacDonald attended Patchogue-Medford High School, where he became president of the student council. He was voted both "most popular" and "most likely to succeed" by his fellow students, and was king of the senior prom.[5]

Towards the end of his eighth grade year, MacDonald became acquainted with Colette Kathryn Stevenson (b. May 10, 1943).[6] He would later recollect he had first observed Colette "walking down the hallway (of Patchogue High School) with her best friend" and that, although he was attracted to both girls, he found Colette more attractive. Approximately two weeks later, they began talking and formed a friendship, with MacDonald soon "asking her out to the movies". The two formed a brief romantic relationship in the ninth grade, with MacDonald later recollecting they fell in love while holding hands on a balcony while watching the movie A Summer Place at the Rialto Theater in Patchogue. He would later reminisce that whenever he or Colette heard the song "Theme from A Summer Place" across the airwaves, "either of us would turn up the radio".[7]

The following summer, while visiting a friend on Fire Island, Colette announced to MacDonald their relationship was over. MacDonald later formed a relationship with a girl named Penny Wells.[8]

Scholarship and marriage

[edit]MacDonald's high school grades were sufficient for him to earn a three-year scholarship at Princeton University, where he enrolled as a premedical student in 1962. By the second year of his studies, MacDonald and Wells had separated. He soon resumed his romantic relationship with Colette,[9] then a freshman at Skidmore College in Saratoga Springs. He would later recollect Colette had grown into a shy young woman with a "slight fear of the world in general" who would rely on his own self-confidence. MacDonald found her timidity touching, and gradually viewed himself as her protector in addition to her boyfriend.[10] The two regularly exchanged letters, and he would frequently hitchhike to Skidmore College to be in her company at weekends. Although MacDonald was dating other women at the time, he resolved to marry Colette upon learning she was pregnant with his child in August 1963. She in turn left college to raise their child.[11]

With the consent of Colette's family, the two married on September 14 in New York City.[12][4] One hundred people attended the service, with the reception held at the Fifth Avenue Hotel. The couple then honeymooned at Cape Cod. Their first daughter, Kimberley Kathryn, was born on April 18, 1964.[13][14]

Medical school

[edit]After his undergraduate work at Princeton, MacDonald briefly worked as a construction supervisor before he moved with his wife and child to Chicago in the summer of 1965, where he had been accepted at Northwestern University Medical School. The couple moved into a small one-bedroom apartment, with Colette committed to maintaining the household and raising their daughter as MacDonald focused on his studies, while also working a series of part-time jobs to assist with family finances. The following year, the family relocated to a middle-class neighborhood. Their second child, Kristen Jean, was born on May 8, 1967.[4][n 1]

Shortly after MacDonald graduated from medical school in 1968, he and his family relocated to Bergenfield, New Jersey as he completed a one-year internship at the Columbia Presbyterian Medical Center in New York, specializing in thoracic surgery. MacDonald later described his internship year as "a horrendous year" for both himself and Colette, adding he frequently worked 36 hours with only 12 hours at home. Consequently, when at home, he was frequently exhausted and had limited interaction with his wife and daughters. At the completion of his internship, MacDonald and Colette vacationed in Aruba before MacDonald joined the Army.[16]

U.S. Army

[edit]MacDonald was commissioned in the United States Army on June 28, 1969,[17] and sent to Fort Sam Houston, Texas to undergo a six-week physician's basic training course. While at Fort Sam Houston, he volunteered to be assigned to the Army's Special Forces ("Green Berets") to become a Special Forces physician.[18][19] He was then assigned to Fort Moore, Georgia (then known as Fort Benning), where he completed their paratrooper training course. Although MacDonald had joined the Army knowing he might be deployed to serve in the Vietnam War, he later learned that, as a Green Beret doctor, he was unlikely to serve overseas.[20]

Fort Bragg

[edit]

In late August,[21][12] MacDonald reported to the 3rd Special Forces Group (Airborne) at Fort Liberty (then known as Fort Bragg), North Carolina to serve as the group's surgeon.[21][n 2] He was joined by his wife and children,[12][23] and the MacDonald family resided at 544 Castle Drive,[24] in a section of the base reserved for married officers and afforded security by military police.[n 3] The couple quickly became popular among their neighbors, although MacDonald and Colette are known to have argued occasionally.[n 4]

By the time the MacDonalds moved into their new apartment at Fort Bragg, Colette had accrued two years of studies, with aspirations to obtain a bachelor's degree in English literature and teach part-time. Both daughters had developed distinctive personalities: Kimberley being markedly feminine, intelligent, and shy; Kristen a boisterous tomboy who would "run over and crack someone" if she observed her older sister being bullied by other children.[26]

On December 10, the 3rd Special Forces Group was deactivated,[27] and MacDonald was transferred on base to Headquarters and Headquarters Company, 6th Special Forces Group (Airborne), 1st Special Forces,[17] to serve as a preventive medical officer.[28]

Shortly before Christmas 1969, with his wife approximately three months pregnant with their third child and first son, MacDonald bought his daughters a Shetland pony, anticipating the family would soon relocate to a farm in Connecticut.[29] He kept this purchase a secret from his wife and children, and he and his stepfather-in-law drove them to the stable as a surprise on Christmas Day.[n 5] His daughters chose to name the pony "Trooper".[31] The same month, Colette is known to have penned a letter to college acquaintances in which she described her life as "never [being] so normal or happy", adding she and her husband were content, that their baby son was due to be born in July, and her family would be complete.[32]

By 1970, MacDonald had earned the rank of captain. He was planning to study advanced medical training at Yale University upon completion of his tour of duty as a Green Beret doctor.[33]

February 16–17, 1970

[edit]On the afternoon of February 16, MacDonald took his daughters to feed and ride the Christmas pony he had bought them. The trio then returned home at about 5:45 p.m. MacDonald then showered, and changed into an old pair of blue pajamas. After the family ate supper, Colette left the household to attend an evening teaching class at Fort Bragg's North Carolina University extension.[34]

According to MacDonald, he then played "horsey": allowing his daughters to ride upon his back as if he was their Shetland pony for a short while before he had put Kristen to bed at approximately 7 p.m. as Kimberley played a game on the coffee table.[35] He then slept for an hour before watching Kimberley's favorite television show, Laugh-In, with her before his older daughter also went to bed. Colette returned home at 9:40 p.m., and the couple sat on the couch watching television together before Colette decided to go to bed midway through The Tonight Show Starring Johnny Carson. MacDonald had himself fallen asleep in the living room in the early hours of the following day.[36]

Murders

[edit]

At 3:42 a.m. on February 17, 1970, dispatchers at Fort Bragg received an emergency phone call from MacDonald, who faintly spoke into the receiver: "Help! Five forty-four Castle Drive! Stabbing! ... Five forty-four Castle Drive! Stabbing! Hurry!" The operator then heard the sound of the receiver clatter against a wall or floor.[37]

Within ten minutes, responding military police had arrived at the address, initially believing they were responding to a domestic disturbance. They found the front door closed and locked and the house dark inside. When no one answered the door, they circled to the back of the house, where a police sergeant discovered the back screen door closed and unlocked and the back door wide open. Upon entering, the sergeant walked into the master bedroom before running to the front of the house, shouting, "Tell them to get Womack, ASAP!"[37]

Colette MacDonald was discovered sprawled on the floor of the master bedroom. She lay on her back, with one eye open and one breast exposed. She had been repeatedly clubbed about her body, with both her forearms later found to be broken. The pathologist would note these wounds had likely been inflicted as Colette had raised her arms to protect her face. In addition, she had been stabbed 21 times in the chest with an ice pick and 16 times about the neck and chest with a knife, with her trachea severed in two places.[38] A bloodied and torn pajama top was draped upon her chest, and a paring knife lay beside her body.[37] Beside her, Jeffrey MacDonald was found lying face-down, alive but wounded, with his head on Colette's chest and one arm around her neck. As military personnel approached, he whispered: "Check my kids! I heard my kids crying!"[37]

Five-year-old Kimberley was found in her bed, having been repeatedly bludgeoned about the head and body and stabbed in the neck with a knife between eight and ten times. She lay on her left side. Her skull had been fractured from at least two blows to the right side of her head, and one wound to her face had caused her cheekbone to protrude through her skin.[39] The wounds inflicted to Kimberley's head were sufficiently severe in nature to have caused bruising to her brain, coma, and death soon after infliction.[40]

Across the hallway, two-year-old Kristen was found in her own bed, also lying on her left side, with a baby bottle close to her mouth.[41] She had been stabbed 33 times across the chest, neck, hands, and back with a knife and 15 times with an ice pick. Two knife wounds had penetrated her heart, and the ice pick wounds were noted to be shallow. The injuries to her hands were likely defense wounds.[42] On the headboard of the MacDonalds' marital bed, the word "PIG" was written in eight inch capital letters. The blood used to write this word was later determined to belong to Colette.[43][44][45]

Having received impromptu resuscitation, MacDonald sat upright, then exclaimed: "Jesus Christ! Look at my wife! I'm gonna kill those goddamned acid heads!"[46] He was immediately taken to nearby Womack Hospital, shouting, "Let me see my kids!" as he was carried out of his home on a stretcher.[37]

MacDonald's account

[edit]Taken to the Womack Army Medical Center, medical staff discovered the wounds MacDonald had suffered were much less numerous and severe than those inflicted upon his wife and children. He had suffered cuts, bruises, and fingernail scratches to his face and chest, although none of these wounds were life-threatening or required stitches. MacDonald was also found to have a mild concussion. He had also received a single stab wound between two ribs on his right torso. This wound was described by a staff surgeon as a "clean, small, sharp" incision measuring five-eighths of an inch in depth, and had caused his lung to partially collapse. MacDonald was released from the hospital after nine days.[47]

Questioned by the Criminal Investigation Division (CID), MacDonald claimed that at about 2:00 a.m. on February 17, he had washed the evening's dinner dishes before deciding to go to bed, although because his younger daughter, Kristen, had wet his side of the bed, he had taken her to her own bed.[48] Not wishing to wake his wife to change the sheets, he had then taken a blanket from Kristen's room and fallen asleep on the living room couch.[37] According to MacDonald, he was later awakened by Colette and Kimberley's screams, and Colette shouting: "Jeff! Jeff! Help! Why are they doing this to me?"[49] As he rose from the couch to go to their aid, he was attacked by three male intruders, one black and two white. The shorter of the two white men had worn lightweight, possibly surgical, gloves. A fourth intruder he described as a white female with long blonde hair (possibly a wig)[50] and wearing high heeled, knee-high boots and a white floppy hat partially covering her face. This individual stood nearby holding a lighted candle, chanting, "Acid is groovy, kill the pigs!"[51]

MacDonald claimed the three males then attacked him with a club and ice pick, with the female intruder shouting "Hit 'em again!"[52] During the struggle, his pajama top was pulled over his head to his wrists and he had used this bound garment to ward off thrusts from the ice pick although eventually, he was overcome by his assailants and knocked unconscious in the living room end of the hallway leading to the bedrooms. When he had regained consciousness, the intruders had left the house.[53] He had then stumbled from room to room, attempting mouth-to-mouth resuscitation upon each of his daughters, to no avail,[54] before discovering his wife. He had pulled a small paring knife from Colette's chest which he then tossed onto the floor, attempted in vain to find her pulse, then draped his pajama jacket over her body. Then he had phoned for help.[55]

Initial investigation

[edit]Within minutes of the discoveries at Castle Drive, military police were instructed to check the occupants of all vehicles in and around Fort Bragg, seeking two white men, one black man, and a white woman with blonde hair and a floppy hat in an effort to apprehend the four intruders MacDonald alleged had attacked him and his family. Despite these efforts, military police failed to locate the four intruders, and the initiative was abandoned by 6:00 a.m.[56]

Shortly after daylight on February 17, investigators recovered the murder weapons just outside the back door. These instruments were an Old Hickory kitchen knife, an ice pick, and a 31-inch long piece of lumber with two blue threads attached with blood; all three were quickly determined to have come from the MacDonald house, and all had been wiped clean of fingerprints.[57][n 6] MacDonald later claimed to have never seen these items before.[25]

Scrutiny

[edit]As Army investigators studied the physical evidence, the Army CID quickly came to disbelieve MacDonald's account, as they found very little evidence to support his version of events. Although MacDonald was trained in unarmed combat,[58] the living room where he had supposedly fought for his life against three armed assailants showed few signs of a struggle apart from a coffee table that had been knocked onto its side with a pile of magazines beneath the edge, and a flower plant that had fallen to the floor.[43] Questioning of the MacDonalds' neighbors revealed they had heard no sounds of a struggle or disturbance within the household in the early hours, but had heard Colette shouting in a loud and angry voice. The 16-year-old daughter of these neighbors—who occasionally babysat for the family—informed investigators the two had seemed taciturn and indifferent to each other in the month prior to the murders.[59][n 7] By February 23, Colonel Robert Kriwanek, the Fort Bragg provost marshal,[61] had advised the FBI to discontinue their search for the four intruders.[62]

In addition to the lack of damage to the inside of the house, no fibers from MacDonald's torn pajama top were found in the living room, where he claimed the garment had been when torn in his struggle with the intruders. However, fibers from the pajama top were found beneath Colette's body and in the bedrooms of both of his daughters, and one fiber from this garment was also found under Kristen's fingernail. A single fragment of skin was recovered from beneath one of Colette's fingernails, although this evidence was later lost.[63] Bloodstained splinters likely sourcing from the section of lumber recovered close to the back door of the apartment were recovered from all three bedrooms of the apartment, but not the room where MacDonald claimed to have been attacked. No blood or fingerprints were found on either telephone MacDonald claimed he had used to call for help after checking each member of his family and attempting to resuscitate them.[64] Furthermore, the bloodstained tip of a surgical glove was also found beneath the headboard where the blood inscription was written; this glove was identical in composition to a medical supply MacDonald invariably kept in the family kitchen.[37]

Although it had rained on the night of February 16–17 and MacDonald also specifically claimed the female intruder's boots were "all wet", with rainwater "just dripping off them",[65] the sole footprint observed at the scene was a bloody bare footprint located in Kristen's bedroom, leading from the child's bed in the direction of the doorway.[66]

Forensic analysis

[edit]By mid-March, the CID had obtained the results of forensic testing of the blood, hair, and fiber samples within 544 Castle Drive that contradicted MacDonald's accounts of his movements and further convinced investigators of his guilt. For example, Kimberley's blood was also found on his pajama top, even though MacDonald had claimed he was not wearing this garment while in her room attempting resuscitation.[67] MacDonald's own blood was located in significant quantities in only two locations: in front of the kitchen cabinet containing rubber gloves, and upon the right side of a hallway bathroom sink.[68]

Investigators also questioned why Colette's blood was found in Kristen's room, although all three victims were found in separate rooms, suggesting they had been attacked separately. Moreover, although blood evidence indicated Kimberley had been attacked as she entered the master bedroom, investigators questioned why home intruders would bother to carry her back to her bedroom to continue their attack.[63]

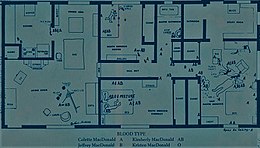

The four members of the MacDonald family had different blood types: a statistical anomaly that assisted investigators in determining the movements of each member of the household and their subsequent theory as to a likely scenario of the unfolding events.[69][n 8] Upon the assumption the four individuals discovered by responding military police were the only four people in the house in the early hours of February 17, investigators were able to reconstruct a likely scenario of the chain of events that had unfolded via blood typing and the nature and severity of the wounds discovered upon each individual.[37]

Forensic reconstruction

[edit]An argument or fight between MacDonald and Colette began in the master bedroom, possibly over the issue of Kristen's repeatedly wetting his side of the bed while sleeping there, or his adultery.[71][n 9] Investigators speculated that the argument turned physical and she had probably hit him on the forehead with a hairbrush, which resulted in a mark on his forehead which failed to break his skin. As he retaliated by hitting her, first with his fists and then beating her with a piece of lumber, Kimberley, whose blood and brain serum were found in the doorway, may have walked in after hearing the commotion and was struck at least once on the head, possibly by accident. Believing Colette dead, MacDonald carried the mortally wounded Kimberley back to her bedroom. After stabbing her, MacDonald then proceeded to Kristen's room, carrying the club he had used to bludgeon Kimberley, intent on disposing of the last remaining potential witness. Before he could do so, Colette, whose blood was found on Kristen's bed covers and on one wall of her room, apparently regained consciousness, stumbled into her younger daughter's bedroom and threw her own body over Kristen in a desperate effort to protect her. After killing both of them, MacDonald then wrapped Colette's body in a sheet and carried her body to the master bedroom, leaving a smudged footprint matching her blood type as he exited Kristen's bedroom.[72][n 10]

CID investigators then theorized that MacDonald attempted to cover up the murders, using articles on the Manson Family murders that he had recently read in the March 1970 issue of Esquire investigators had found in the living room.[n 11] Putting on surgical gloves from a medical supply in the kitchen closet,[74] he went to the master bedroom, where he used Colette's blood to write the word "PIG" on the headboard.[9] MacDonald then laid his torn pajama top over her dead body and repeatedly stabbed her in the chest with an ice pick, then discarded the weapons close to the back door of the property after wiping them clean of fingerprints. Finally, MacDonald took a scalpel blade from the supply closet, entered the adjacent bathroom, and stabbed himself once in the chest while standing beside the sink before disposing of the surgical gloves. He had then used the family telephone to summon an ambulance before lying down beside Colette's body as he waited for the military police to arrive.[75]

Interrogation

[edit]On April 6, 1970, Army investigators formally cautioned, then interrogated MacDonald. He was first offered the chance to recount his version of events, and recounted his claims of being attacked by four intruders, with whom he grappled before falling to the ground, observing "the top of some boots" and being rendered unconscious before regaining consciousness, experiencing symptoms of pneumothorax, in the hallway after the intruders had left.[76]

Investigators were unconvinced of MacDonald's accounts. Midway through questioning, MacDonald was asked the question about his stab wounds by CID Investigator William Ivory: "You didn't do it yourself, did you?" This question prompted MacDonald to deny the accusation before referencing his puncture wound and his having to persuade hospital doctors to insert a chest tube into his body as he was sure his lung was punctured. Questioning then focused upon the crime scene and results of the forensic testing. MacDonald denied any of the murder weapons had originated from his household, despite the fact the section of lumber matched wood from Kimberley's closet.[n 12] He also claimed to be unaware of how the fiber and blood evidence contradicted his accounts of his movements and actions.[78]

"This weapon was used on Colette and Kim. It's a brutal weapon. We had three people that were over-killed, almost. And yet... they leave you alive. While you were laying there in the hallway, why not give you a good [blow] or two from behind the head with that club and finish you off? You saw them eye to eye. They don't know that you wouldn't be able to identify them at a later date. Why leave you there alive?"

Investigator Robert Shaw then questioned MacDonald as to the lack of disorder and damage within the household, and the lack of any motive, stating that in the investigators' experience, had four intruders embarked on a murderous frenzy within a small household, they would expect to encounter evidence such as "busted furniture and broken mirrors and bashed-in walls", but the only signs of the struggle were the top-heavy living room coffee table, which had not flipped over all the way in the midst of his struggle, and a flower pot beside the table with the plant upon the carpet and the pot standing upright.[80] MacDonald was unable to offer a plausible explanation for this observation, and also claimed to be unaware how Kimberley's blood and brain serum were recovered from the master bedroom.[81]

Following a short break, questioning resumed the same afternoon. Investigator Franz Grebner listed further physical discrepancies between MacDonald's account and the forensic evidence, repeatedly stating all the facts pointed to his having staged the crime scene. MacDonald was unable to offer a plausible explanation to this questioning before abruptly accusing Grebner of having "run out of ideas" and attempting to frame him to maintain a 100% solved homicide rate. In response, Grebner stated, "We have all this business here that would tend to indicate that you were involved in this rather than people who came in from the outside and picked 544 Castle Drive and went up there and were lucky enough to find your door open."[82]

When investigators asked MacDonald to submit to a polygraph test to verify his accounts, he readily agreed, although within ten minutes of the conclusion of the interview, he called investigators to state he had changed his mind, and would not submit to any polygraph testing.[83][63]

Formal charges

[edit]On the evening of April 6, MacDonald was relieved of his duties and placed under restriction, pending further inquiries. The following day, he was assigned an army lawyer. At the recommendation of his mother, on April 10, he instead hired a flamboyant civilian defense attorney, Bernard Segal, to defend him. Less than a month later, on May 1, the Army formally charged MacDonald with three counts of murder.[84][85] That same day, MacDonald penned a letter to Colette's mother and stepfather professing his innocence, emphasizing the Army would "never admit" their error, and speculating his wife's soul may hold "infinite patience and understanding" of his current legal predicament.[86]

Army hearing

[edit]An initial Army Article 32 hearing into MacDonald's possible guilt, overseen by Colonel Warren Rock, convened on July 6, 1970. This hearing lasted until September.[87]

MacDonald's lawyer, Bernard Segal, adopted an offensive strategy on behalf of his client at this hearing, citing numerous examples of incompetence on behalf of the Army CID, stating that they had clumsily and unprofessionally "trampled all over" the crime scene during their examination of the house, obliterating any traces of evidence the perpetrators might have left and losing vital pieces of evidence including a single thread found beneath Kimberley's nail, MacDonald's pajama trousers,[88] four torn tips of rubber surgical gloves found in the master bedroom, and a single layer of skin found beneath one of Colette's fingernails.[89] Segal elicited several examples of incompetence from military police and responding personnel, including testimony revealing that an ambulance driver had stolen MacDonald's wallet from the living room,[90] and a pathologist who testified to having failed to obtain the children's fingerprints for comparison at the crime scene.[91]

The first witness to testify in MacDonald's defense, responding military policeman Kenneth Mica, testified that on the way to answering MacDonald's emergency call on the night of the murders, he had observed a blonde woman with a wide-brimmed hat standing on a street corner approximately half a mile from the MacDonald home. He noted that this sighting was unusual, given the late hour and the weather.[n 13] Mica also testified that, contrary to instruction, an ambulance driver had placed the tilted flower pot upright while at the crime scene.[93]

Colonel Rock also testified that he himself went to the scene of the crime and tipped the coffee table over, with it striking the side of a rocking chair and coming to rest on its edge. Rock also noted the fact that if no wet footprints and mud were found at the crime scene belonging to the alleged intruders, that meant the crime scene investigators had also failed to find any evidence of the large numbers of military police and civilians who also walked around the house.[94]

Suspect identification

[edit]In August, Segal was approached by a deliveryman named William Posey, who claimed the blonde woman MacDonald stated had attacked his family might have been a local 17-year-old drug addict and police informant named Helena Werle Stoeckley. According to Posey, Stoeckley had been in the company of "two or three" young males in a car parked outside her apartment at approximately 4:00 a.m. on the morning of the murders. Posey also claimed Stoeckley had ceased wearing her boots and floppy hat subsequent to February 17, and had dressed in black on the date of the funerals, also stating to him she "[did not] remember what [she] did" on the date of the murders. Posey later relayed this information at the hearing, adding that Stoeckley had informed him months later that she and her boyfriend could not marry until "we go out and kill some more people".[95][n 14]

Stoeckley was located and questioned regarding her whereabouts on February 17. Her answers were vague and self-contradictory. She recalled being in the company of her boyfriend, Gregory Mitchell, on the night of February 16, and going "out for a ride" in a car in the early hours of the following day, "driving aimlessly", but claimed to have been "so far out" on mescaline that she could not say for sure whether she had been at the house or not.[98] Although witnesses had claimed Stoeckley had admitted her involvement in the murders, with several also remembering her wearing clothing similar to that described by MacDonald on the date in question, she was not subpoenaed to testify.[97][99] Procedural irregularities regarding investigative conduct into Stoeckley were also highlighted by Segal at this hearing.[100]

MacDonald's testimony

[edit]Following favorable character testimony from several acquaintances and a military psychiatrist, MacDonald testified for three days in mid-August. Sections of his testimony contradicted what he had informed investigators on April 6, including his claim on this occasion to have actually moved Colette's body, having found her "a little bit propped up against a chair" before he "just sort of laid her flat" on the floor. He also stated that, possibly because of his surgical background, he had "sort of rinsed off [his] hands" as he checked his own injuries in the bathroom before calling for help. Referencing the type B blood found in the kitchen, MacDonald testified that he "may have" also washed his hands in the kitchen sink "for some reason" prior to making the phone call to emergency services. Contrary to medical reports and his earlier accounts, he also claimed to have located two bumps on the back of his head and "two or three" puncture wounds in his upper left chest, other wounds to his right bicep, and approximately ten ice pick wounds to his abdomen on February 17 or 18—all of which had healed without treatment and none of which had required surgery.[101]

Questioned in regards to his infidelity, MacDonald admitted he had been unfaithful on two occasions, but insisted Colette had not known about either affair. He also claimed their time at Fort Bragg had been the most content of their married life.[102]

MacDonald's testimony was followed by that of a clinical psychologist, who testified as to conclusions of a series of tests he had conducted on MacDonald. This expert testified that the tests revealed an extraordinary absence of anxiety, depression, and anger in MacDonald with regard to the loss of his family, and that his report concluded he was "able to muster massive denial or repression" to such a degree that the "impact of the recent events in his life has been blunted". Furthermore, this extreme psychological response would likely see an individual convey himself as "victimized" and "perhaps, somewhat of a martyr".[103]

Initial dismissal of charges

[edit]To the chagrin of Colonel Kriwanek, on October 13, 1970, Colonel Rock issued a report recommending that charges be dismissed against MacDonald as insufficient evidence existed to prove his guilt, adding his belief no truth existed in the charges, and that the nature of the murders led him to believe the perpetrator(s) were either insane or under the influence of drugs. Rock also recommended that civilian authorities further investigate Stoeckley. Later the same month, all charges were formally dismissed, although a new CID investigation tasked with finding the murderer(s) was assembled in February 1971, with MacDonald still considered a suspect.[104]

In December, MacDonald received an honorable discharge from the Army and initially returned to New York City, where he briefly worked as a doctor before relocating to Long Beach, California in July 1971[35][105] in an effort to "put the past" behind him and to distance himself from the "constant reminders" of his wife and daughters.[106] He obtained employment as an emergency room physician at the St. Mary Medical Center,[107] frequently working long hours.[35] He also became an instructor at the UCLA medical school, a medical director of the Long Beach Grand Prix, a lecturer on the subject of the recognition and treatment of child abuse, and a participant in the development of a national cardiopulmonary resuscitation training program.[108] MacDonald lived in a $350,000 Huntington Beach condominium apartment, and is known to have lived a promiscuous lifestyle prior to forming a long-term relationship with a 22-year-old airline stewardess named Candy Kramer in the late 1970s.[109]

In the years immediately following the dismissal of the murder charges, MacDonald received an abundance of emotional and public support.[110] He also wrote letters to several magazines and newspapers detailing his willingness to further publicize the background and legalities of his case.[111]

Further investigation

[edit]Within days of the dismissal, MacDonald began granting press interviews and media appearances, most notably on the December 15, 1970, episode of The Dick Cavett Show, during which he appeared flippant as he complained about the Army investigation and their focus on him as a suspect. On this occasion he claimed to have sustained 23 wounds—some of which he claimed were "potentially fatal".[112]

MacDonald's stepfather-in-law, Alfred Kassab, had initially believed in his stepson-in-law's innocence.[14][n 15] Both he and Colette's mother, Mildred, had testified in support of MacDonald during the Army's Article 32 hearing,[114] informing the press, "My wife and I feel very strongly about Captain MacDonald's innocence. After all, it was our daughter and two grandchildren who were butchered."[9] However, by November 1970, Kassab had grown suspicious of MacDonald's repeated reluctance to provide him with a copy of the 2,000-page transcript of the Article 32 hearing.[n 16] In an apparent effort to discourage Kassab's efforts to obtain a copy of this transcript in his pursuit of the killers, MacDonald told his stepfather-in-law that he and some Army colleagues had actually tracked down, tortured, and eventually murdered one of the four alleged murderers.[9] Kassab's suspicion greatly increased following MacDonald's casual and dismissive demeanor on The Dick Cavett Show—just days after he had himself hand-delivered 500 copies of an eleven-page letter to members of Congress requesting a congressionally mandated re-investigation of the murders—and he and his wife publicly turned against MacDonald.[116][n 17]

Kassab successfully obtained a copy of the Article 32 transcript from the Army in February 1971. He repeatedly studied the document, realizing MacDonald's claims were inconsistent with the physical facts and concluding his account was nothing more than a "tissue of lies" that repeatedly contradicted the known facts of the case.[9] One example was MacDonald's assertion that he had sustained life-threatening injuries—including ten ice pick wounds—during the alleged physical assault at the hands of his assailants; Kassab had met MacDonald in the hospital less than 18 hours after the attack and had observed him sitting up in bed, eating a meal, with very little bandaging or other medical dressing on his body. An examination of hospital records confirmed MacDonald had received no such wounds.[37] Kassab also discovered that, within weeks of the murders of his family, MacDonald had begun dating a young woman employed at Fort Bragg.[118] He and his wife also later discovered that, by 1969, he had rekindled his relationship with Penny Wells.[119]

With the cooperation of Colonel Kriwanek and other Army investigators, Kassab visited the crime scene for several hours in order to compare the physical evidence against MacDonald's testimony in March 1971.[n 18] This personal assessment ultimately convinced Kassab of MacDonald's guilt, and he resolved to devote his life to pursuing all legal avenues to bring MacDonald to justice.[120] As the Army's investigation was completed, the only way Kassab could bring MacDonald to trial was via a citizen's complaint filed through the United States Department of Justice. He filed this complaint in early 1972; however, because the murders had occurred while MacDonald was serving in the Army, and he had since been discharged, the citizen's complaint was declared moot. The FBI refused to take on the case.[n 19]

Legal maneuvers

[edit]Between 1972 and 1974, the case remained trapped in limbo in the Department of Justice as legal issues were raised and debated over whether sufficient evidence and probable cause existed for indictment and prosecution.[122][123] On April 30, 1974, the Kassabs, their attorney, Richard Cahn, and CID agent Peter Kearns presented a citizen's complaint against MacDonald to US Chief District Court Judge Algernon Butler, requesting the convening of a grand jury to indict MacDonald for the murders.[124] The following month, Justice Department attorney Victor Woerheide ruled the case worthy of prosecution.[125]

Grand jury

[edit]On August 12, 1974, a grand jury convened before U.S. District Judge Franklin Dupree in Raleigh, North Carolina, to hear the legal proceedings. Seventy-five witnesses were called to testify. MacDonald was the first individual to testify at this hearing. His testimony lasted five days, during which he conceded that although he had publicly resolved to pursue all legal avenues following the 1970 dismissal of the murder charges against him, and to hire investigators, he had failed to do so. Nonetheless, he was adamant he had made his own efforts to identify the perpetrators and to locate Helena Stoeckley. He also claimed the numerous fabrications he had provided to the Kassabs and to sections of the media in the intervening years were to placate his in-laws, and that he had received more stab and puncture wounds to his body than recorded in contemporary medical records (which he blamed on malpractice).[n 20] When asked by Victor Woerheide if he would submit to either a polygraph or sodium amytal test to verify his version of events, MacDonald read a statement prepared by his attorneys denying their request.[126]

Other witnesses to testify included surgeons on duty at Womack Hospital who had examined MacDonald and who testified that, aside from his punctured lung, MacDonald was "not in any great danger, medically", and that, save for a superficial stab wound to his upper left arm and abdomen, MacDonald had no other stab wounds to his body.[127] A reporter who had covered the Article 32 hearing and who interviewed MacDonald after the charges were dropped also stated that, in his experience, individuals under the influence of LSD seldom become violent and that, by contrast, those who consume amphetamines frequently do.[128]

On December 12, a former chief of psychiatry who had also testified at the Article 32 hearing, Bruce Bailey, testified. Bailey stated that, when discussing his family and the events surrounding their deaths with him, MacDonald would occasionally "become emotional, become tearful, but he recovered quickly". Bailey also testified he found MacDonald to be a controlling individual who was "extremely dependent on what others thought of him" and that he would often launch into a verbal "tirade" to allow his deep-seated emotions to become expressed by other means. When questioned as to whether MacDonald suffered from a mental disorder, Bailey testified he did not, although he could not discount the possibility of him murdering members of his family in a situation of extreme stress.[129] This testimony was followed by a Philadelphia-based psychologist who conceded that, had MacDonald committed such an act of violence, he would successfully "completely block" the episode from his mind.[130]

The chief of the FBI's crime laboratory chemistry section, Paul Stombaugh, then testified the pajama top placed over Colette's body had been heavily bloodstained before the garment was torn, and that—contrary to MacDonald's claims—a lack of tearing at the edges of these holes proved that all 48 holes within this item of clothing had been inflicted while the garment was stationary, rather than in motion. Stombaugh also testified all the cuts within all garments other than the pajama top had been inflicted with the Old Hickory kitchen knife found outside the family home and not the paring knife he claimed to have removed from Colette's body, that the majority of this blood had belonged to Colette, and her blood had transferred onto the garment on at least four locations prior to the garment being torn.[131] Furthermore, the club used to bludgeon Colette and Kimberley, which MacDonald had denied any knowledge of, had also been sawed from one of the mattress slats in Kimberley's bedroom, and a single hair found in Colette's right palm had been sourced from her own body and not a blonde-haired intruder.[132]

Further testimony

[edit]MacDonald was recalled to testify before the grand jury on January 21, 1975. On this occasion, he was markedly arrogant and sarcastic when questioned with regards to issues such as his infidelity or the prosecution's illustration of forensic contradictions between his version of events and the physical evidence, on one occasion shouting, "I have no idea! I don't even know what crap you're trying to feed me!" in response to a question as to how his blood and Colette's blood had transferred onto a sheet taken from Kristen's bedroom into the master bedroom. He also refused to discuss the results of a private polygraph test to which he had consented in 1970, the results of which had been given to Bernard Segal, indicating he would have to speak with his attorney on this matter before consenting to this line of inquiry.[133]

Following a brief recess, MacDonald read a statement prepared by his attorneys denying the prosecution's request to discuss the results of his 1970 polygraph examination, contending Woerheide had violated attorney-client privilege. He then read his own statement to the jury, claiming "five long years" had passed since the murder of his family and his efforts to start life afresh, and that the questions posed by the prosecution were ones he had had to "live with for five years".[134]

Indictment

[edit]On January 24, 1975, the grand jury formally indicted MacDonald on three counts of murder.[135] Within the hour, he was arrested in California. On January 31, he was freed upon a $100,000 bail raised by friends and colleagues, pending disposition of the charges, although he was arraigned on May 23, and pleaded not guilty to the murders on this date. On July 29, Judge Dupree denied the double jeopardy and speedy trial arguments successively filed by his attorneys, and allowed the proposed trial date of August 18, 1975, to stand, although the Fourth Circuit Court of Appeals ruled to stay the proceedings on August 15. The panel of this court ordered the indictment dismissed on the grounds of a defendant's right to a speedy trial on January 23, 1976.[n 21] MacDonald himself later claimed to weep "tears of relief rather than tears of joy" upon hearing this news, and later recollected to return to a "big celebration" that his ordeal was now over.[137]

"The story, as [MacDonald] told it, had to be a fabrication. It could not have happened the way he said it happened. None of his story holds together. I mean, none of what he says he did. He claims to have been attacked in the living room. He claims to have sustained ten ice pick wounds. Now, those ten ice pick wounds, nobody has ever seen. No doctor in a hospital ever saw them."

The Government appealed to the United States Supreme Court, which ruled on May 1, 1978, that the Fourth Circuit erred in dismissing the indictment for a speedy trial violation before the case had been tried.[138] In response to this decision, Alfred Kassab informed the press he and his wife welcomed the developments, stating, "It has been [a] tremendous personal pressure to have someone running around that you are convinced killed your daughter and grandchildren."[139][n 22] On October 27, the Fourth Circuit Court of Appeals rejected MacDonald's double jeopardy arguments.[141] The Supreme Court refused to review this decision on March 19, 1979.[142]

Trial

[edit]MacDonald was brought to trial on July 16, 1979, charged with three counts of murder. He was tried in Raleigh, North Carolina, before Judge Dupree, and pleaded not guilty to the charges. MacDonald was defended by Bernard Segal and Wade Smith; James Blackburn and Brian Murtagh prosecuted the case. Initial jury selection began on this date, and would continue for three days.[143]

Although MacDonald's lawyers had been confident of an acquittal, there were successive rulings against the defense. The first such ruling was Judge Dupree's refusal to admit into evidence a 1979 psychiatric evaluation of MacDonald, which suggested that an individual of his personality and mindset was highly unlikely to be capable of killing his family. Dupree justified this refusal by stating that, as MacDonald's attorneys had not entered an insanity plea for their client, he did not wish for the trial to be hindered by opinionated and contradictory psychiatric testimony from prosecution and defense witnesses.[144] A further defense setback was the judge's ruling against a motion to suppress the introduction of MacDonald's pajama top as evidence.[145]

On the first day of the trial, Judge Dupree allowed the prosecution to admit into evidence the March 1970 copy of Esquire magazine, found in the MacDonald house, part of which contained the lengthy article relating to the Manson Family murders. However, Dupree also refused the prosecution's request to allow any sections of the earlier Article 32 transcripts from MacDonald's 1970 Army hearing to be produced as evidence, ruling that as the current trial was a civilian trial and the Article 32 military hearing held several reports from the military investigators, which had suggested that MacDonald had murdered his family in a drug-induced rage, this evidence was also opinionated.[146]

Opening statements

[edit]In his opening statement to the jury, delivered on July 19, James Blackburn outlined the burden of proof the prosecution faced in proving MacDonald's guilt, that the prosecution intended to meet this burden, and that the murders had been committed with malice aforethought. Blackburn then outlined the prosecution's intention to outline both physical and circumstantial evidence indicating MacDonald's guilt, and to introduce numerous witnesses, imploring the jurors to "listen to the evidence that comes from the witness stand, [to] examine the evidence, as it is shown to you, and reach your own conclusion". Blackburn finished his opening statement by stating to the jurors: "Basically, we believe that the physical evidence points to the fact that, unfortunately, one person—not two, three, four or more—killed Colette, Kimberley, and Kristen, and that person is the defendant."[147]

Wade Smith then argued on behalf of the defense. Smith referenced the events of February 17, 1970, the Army investigation and subsequent dismissal of all charges. Repeatedly emphasizing the case had occurred over nine years ago, and that, in the intervening years, "Jeff" had done his utmost to rebuild his life while "others" would not allow him to forget his painful past, their client had now been brought to trial to face the charges of murdering his wife and children, Smith emphasized to the jurors their ability to relieve their client of his ongoing ordeal by acquitting him of all charges.[147]

Testimony

[edit]One of the chief prosecution witnesses to testify was Paul Stombaugh, whom the prosecution summoned to testify on August 7. Stombaugh demonstrated to the jurors how MacDonald's pajama top had been pierced by 48 small, smooth, and cylindrical ice pick holes after the garment had been placed atop his wife's chest.[98] Stombaugh contended that, in order for the holes to have been as smooth and devoid of fraying or tearing, the garment would have had to remain stationary, an extremely unlikely occurrence if, as MacDonald contended, he had wrapped it around his hands to defend himself from blows from an attacker wielding an ice pick or club. Furthermore, Stombaugh demonstrated that by folding the garment in the manner depicted in the crime scene photographs, all 48 holes could have been made by 21 thrusts of the ice pick through the garment, and in an identical pattern, implying Colette had been repeatedly stabbed through the pajama top while the garment was lying on her body.[148] Although Segal subjected Stombaugh to a harsh cross-examination—repeatedly raising his voice as he challenged Stombaugh's credentials and forensic methods—Stombaugh remained steadfast as to his conclusions.[149]

A further piece of damaging evidence against MacDonald was an audio tape made of the April 6, 1970 interview by military investigators, which was played in the courtroom immediately after the jurors had returned from visiting the still-intact crime scene. The jury heard MacDonald's matter-of-fact, indifferent recitation of the murders. They heard him become angry, defensive, and emotional in response to suggestions by the investigators that he had committed the murders. He asked the investigators why would they think he, who had a beautiful family and "everything going for [him]", could have murdered his family in cold blood for no reason. The jury also heard investigators later confront him with their knowledge of his extramarital affairs, to which MacDonald murmured, "Oh... you guys are more thorough than I thought."[150][n 23]

Despite earlier rulings against the defense counsel, the prosecution was also hampered by the lack of an obvious motive for MacDonald to have committed the murders. He had no history of violence or domestic abuse against his wife or children. The defense also argued the crime scene was hopelessly compromised during the investigation and potential evidence either was destroyed, was lost, or remained uncollected.[152]

MacDonald's defense attorneys also called several favorable character witnesses, plus a forensic expert named James Thornton, to the stand. Thornton attempted to rebut Stombaugh's contention that the pajama top was stationary on Colette's chest, rather than wrapped around MacDonald's wrists as he warded off blows, stating that he had attempted to stab a pajama top wrapped around a ham with an ice pick as an assistant moved the item back and forth, resulting in perfectly cylindrical holes with no tearing around the edges of the garment.[153]

Following Thornton's testimony, prosecutors Murtagh and Blackburn staged an impromptu re-enactment of the alleged attack on MacDonald. Murtagh wrapped a pajama top of the same material around his hands and attempted to fend off a series of blows that Blackburn attempted to inflict on him with the ice pick used in the murders. The resulting ice pick holes in the pajama top were jagged and elongated, not smoothly cylindrical like the ones within the garment recovered upon Colette's body. Furthermore, Murtagh received a small wound on his right arm. MacDonald had received no defensive wounds on his arms or hands consistent with a struggle. In addition, aside from a small smear of blood discovered upon the Esquire magazine and a single speck of blood upon MacDonald's spectacles, no other traces of blood were recovered from the room in which MacDonald claimed to have fought for his life.[154]

Helena Stoeckley

[edit]One of the final defense witnesses Segal subpoenaed to testify was Helena Stoeckley. Intent on extracting a confession from her that she had been one of the intruders MacDonald claimed had entered his house, murdered his family and attacked him,[155][n 24] Segal talked to Stoeckley in private for over two hours, attempting to persuade her to confess to end MacDonald's years of "suffering unjustly"—also promising her immunity from prosecution due to the expiration of the statute of limitations. Stoeckley repeatedly informed Segal she was unable to help him. She also denied ever having seen MacDonald, and refused to testify to acts she was adamant she did not commit.[1][156]

Under oath, Stoeckley denied any culpability in murders, and any knowledge of who may have committed the acts. Stoeckley was insistent that she was unable to recall her whereabouts on the date of the murders; she emphasized her extensive drug use in 1970 and the intervening years, adding that the night of February 16–17, 1970 was "by no means" the first or last night in which she was unable to recall her whereabouts.[157] Following this testimony, Murtagh and Segal alternately argued before Judge Dupree for the dismissal, or introduction of, testimony from several witnesses to whom Stoeckley had earlier allegedly confessed. On August 20, Dupree refused the introduction of this testimony, citing legal trustworthiness requisites and stating the introduction of these witnesses would add no further value to the proceedings than what they had experienced from Stoeckley's own testimony.[96]

Defendant's testimony

[edit]The final witness to testify on behalf of the defense was MacDonald himself, who testified on his own behalf on August 23 and 24.[158]

MacDonald was first questioned by Bernard Segal, who sought to humanize his client in the eyes of the jury. He began his questioning by asking MacDonald about his family. MacDonald described each family member and their individual personalities, stating the family "shared almost everything ... we were all friends. Colette and I shared the children growing up. We shared our life experiences." He also claimed the reason he had never remarried was the fact he was unable to forget his wife and children, whom he thought about daily. Segal then asked MacDonald to recount his family background, his career at Fort Bragg, and his family's general lifestyle in February 1970. He then produced several family photographs and artifacts, asking MacDonald to describe each item or the circumstances surrounding each photograph, and to identify the individual in each image.[35] MacDonald then recounted his life in the years since the deaths of his family, describing his decision to relocate to California as an effort to distance himself from well-wishers and insisting the reason he worked up to eighty hours a week was that it was "easier than sitting and thinking" about his family.[159][n 25]

The following day, James Blackburn cross-examined MacDonald. He outlined every piece of physical and circumstantial evidence recovered at the crime scene which contradicted MacDonald's own accounts of "the assailants" attacking him and murdering his family and instead indicated his own guilt. Blackburn typically began each question with a statement to the effect of: "Dr. MacDonald. Should the jury find from the evidence..."[158] MacDonald was unable to offer any plausible explanations for these discrepancies. For example, he was unable to explain how the piece of lumber used as a weapon came from a mattress slat on Kimberley's bed, but claimed there "may have been" some wood in the utility room, later adding his insistence the club which had struck him across the head was "sort of smooth" and may have been a baseball bat as opposed to a wooden instrument. He also claimed the earlier testimony of Army investigators pertaining to his questioning on April 6, 1970, was unreliable due to the poor conduct of the investigators, and the fact several weeks had elapsed between the murders and his formal questioning.[158]

When questioning MacDonald in regard to various discrepancies in his accounts of his movements, the injuries he sustained, and the positioning of his pajama jacket upon his body throughout the night of the murders with regards to the tearing and fiber evidence sourcing from the garment, Blackburn succeeded in highlighting several discrepancies in MacDonald's accounts by comparison to previous interview transcripts and his current claims, and the contradictions of this testimony with the forensic evidence. In response, Segal repeatedly raised objections to this line of questioning, claiming the discrepancies were misleading. His objections were frequently overruled.[158]

Following a brief recess, Blackburn resumed his cross-examination. On this occasion, he illustrated instances of MacDonald adjusting his testimony regarding having moved his wife's body after learning fibers from his pajama top were found beneath her body. He then asked direct questions regarding the location of blood, fiber, and other physical evidence within his apartment which directly contradicted his accounts of his movements and those of members of his family. Blackburn frequently accompanied these questions with a hypothetical suggestion that "if the jury should find from the evidence"— forensic or circumstantial evidence which contradicted MacDonald's testimony—would he have any plausible explanation for these discrepancies. MacDonald did frequently attempt to rebuff this line of questioning, but was typically unable to offer any explanation for this evidence.[158]

Closing arguments

[edit]On August 28, 1979, both counsels delivered their closing arguments before the jury. James Blackburn argued first, beginning by contrasting the injuries inflicted upon Colette, Kimberley, and Kristen with those suffered by MacDonald. He then outlined the medical testimony which listed the sole serious injury MacDonald had sustained as the pneumothorax wound to his chest, stating that even if the prosecution conceded the wound was potentially life-threatening, the wound was the sole serious injury he had sustained. Referencing the life-and-death struggle MacDonald claimed to have engaged in with the alleged intruders, Blackburn stated the evidence indicated a struggle had occurred in the MacDonald home, but this struggle was between "only one white male and one white female. The white female was Colette and the white male was her husband."

Blackburn then poured scorn on the character witnesses who had earlier testified MacDonald had been a good husband and father, then returned to the evidence, stating: "If we convince you, by the evidence, he did it, we don't have to show you he is the sort of person that could have done it." He then closed his initial argument by stating: "I can only tell you from the physical evidence that... things do not lie. But I suggest that people can, and do."[161]

The following day, Bernard Segal and Wade Smith delivered their closing arguments on behalf of the defense. Segal focused much of his closing argument upon the "campaign of persecution" his client had been subjected to by the legal system for almost a decade in an attempt to frame him for the murder of his family, describing the prosecution's case as a "house built on sand". Portraying MacDonald as a loving husband and father, Segal then emphasized MacDonald's insistence from the outset that four intruders had been responsible for the murders.[162] Segal spoke for over three hours, using virtually all of the defense's allotted time. Blackburn and Murtagh agreed to forfeit 10 minutes of their allocated rebuttal time to allow Smith to make an argument to the jury.[163][n 26]

Following a brief recess, Smith appealed to the jurors to question the lack of an obvious motive for MacDonald to have committed the murders. He referenced the family photographs of MacDonald enjoying the company of his wife and children in the years, and even weeks, before their deaths, stating: "It makes no sense. There is no motive." He then appealed to the jurors to give MacDonald "the peace" he had sought for almost a decade.[162]

In his rebuttal argument, James Blackburn referenced Smith's earlier observation regarding "the unbelievability" of a successful doctor murdering his family, but contended the events of February 17, 1970, occurred "because events overtook themselves too fast... everything else, ladies and gentlemen, we say, in that crime scene, flowed from that moment". He then referred once again to the physical evidence, stating the evidence unequivocally illustrated the chain of events which occurred and which only pointed to MacDonald's guilt. Blackburn closed his rebuttal argument by stating that, although the prosecution was convinced that MacDonald was guilty, they only wished he was not, given the final moments of the victims and "who it was that was going to make them die", adding that the defendant would never have peace.[165]

In a final address to the jury, Judge Dupree informed the panel they had three choices to choose from: To find MacDonald not guilty; to find him guilty of first-degree murder; or guilty of second-degree murder in each case.[166]

Conviction and incarceration

[edit]Shortly after 4:00 p.m. on August 29, 1979, the jury, having deliberated for six-and-a-half hours,[1] announced they had reached their verdict. MacDonald was convicted of one count of first-degree murder in the death of Kristen and two counts of second-degree murder in the deaths of Colette and Kimberley.[145] Four jurors wept as they announced their verdicts, and MacDonald's mother rushed out of the courtroom. MacDonald himself displayed no emotion. Judge Dupree imposed a life sentence for each of the murders, to be served consecutively. Bail was revoked, and MacDonald was temporarily transferred to a Butner County jail, prior to his permanent transferral to the Federal Correctional Institution in Terminal Island, California.[167]

Immediately following the verdict, Alfred Kassab telephoned the family lawyer, Richard Cahn. Kassab thanked the lawyer for his exhaustive efforts over the years, stating: "Hi, Dick, I just got what I wanted. Three life sentences. Thanks for everything. We couldn't have done it without your help!"[168] The Kassabs also informed the press: "This was something that had to be done. Now, we can rest in peace."[166][169]

MacDonald appealed Dupree's bail revocation ruling, requesting that bail be granted pending the outcome of his appeal. This application was rejected on September 7. A further appeal to be freed on bail was rejected by the Fourth Circuit Court of Appeals on November 20.[170]

Post-conviction

[edit]Appeals

[edit]On July 29, 1980, a panel of the Fourth Circuit Court of Appeals reversed MacDonald's conviction, ruling via a 2–1 margin that the nine-year delay in bringing him to trial violated his Sixth Amendment rights to a speedy trial.[171][n 27] He was released on August 22, having posted $100,000 bail, and subsequently returned to work as the Director of Emergency Medicine at St. Mary's Medical Center in Long Beach, California. He would later announce his engagement to his fiancée, Randi Dee Markwith, in March 1982.[172]

Six months later, on December 18, the Fourth Circuit Court of Appeals voted 5–5 to hear the appeal en banc. As a majority did not vote to hear this appeal, the application was accordingly denied, upholding the previous ruling.[173] This decision was appealed, and on May 26, 1981, the US Supreme Court accepted the case for consideration, hearing oral arguments on December 7. On March 31, 1982, the Supreme Court ruled 6–3 that MacDonald's rights to a speedy trial had not been violated, stating the time interval between the dismissal of the military charges and the indictment on civilian charges should "not be considered in determining whether the delay in bringing [MacDonald] to trial violated his right to a speedy trial under the Sixth Amendment". He was rearrested and returned to federal prison and his original sentence of three consecutive life terms reinstated. The following year, MacDonald dismissed Segal as his legal representative.[174]

Defense lawyers filed a new motion for MacDonald to be freed on bail pending appeal, but the Fourth Circuit Court of Appeals refused. His remaining points of appeal—including his contention the evidence presented at trial did not justify the finding of his guilt beyond a reasonable doubt—were heard on June 9, 1982, although his conviction was unanimously affirmed on August 16.[175] Shortly thereafter, MacDonald's licenses to practice medicine in both North Carolina and California were revoked.[176]

MacDonald again appealed this decision, contending his conviction should be overturned due to suppressed exculpatory evidence. Dupree rejected these defense motions on March 1, 1985.[177] The Supreme Court upheld the lower court's decision October 6, 1986. A further defense motion that MacDonald should be granted a new murder trial on the grounds of prosecutorial misconduct was denied on July 8, 1991.[178] This ruling was appealed on the grounds of judicial bias on October 3, but was denied.[179]

A further appeal was argued before the Fourth Circuit Court of Appeals in February 1992. This appeal listed newly discovered evidence which MacDonald contended was suppressed at his trial and which, he claimed, corroborated his exculpatory account of the murders. This appeal contended that, had Judge Dupree permitted this evidence, the jurors would have learned that all of the doctors hired by the defense, who had worked for the Army, or the government at Walter Reed Hospital, had concluded that MacDonald was psychologically incapable of committing such acts of violence.

The court ruled against awarding a new trial on June 2,[180] stating Judge Dupree had acted correctly when he refused to allow the jury to view a transcript of the 1970 Article 32 hearing, and because this was not an insanity trial, he had also acted properly in not allowing the jurors to hear any of the psychiatric testimony. This ruling also stated that Helena Stoeckley's confessions of guilt pertaining to the murders were unreliable and conflicted with the established facts of the case, and accordingly, the judge's ruling against her being allowed to testify at MacDonald's 1979 trial was valid.[n 28]

On September 2, 1997, the district court granted MacDonald's motion to file a supplemental affidavit with the Fourth Circuit Court of Appeals. This affidavit contended that, although several saran fibers found at the crime scene which did not match any evidentiary item recovered had most likely sourced from a doll and not a wig, these fibers were also used in the manufacture of human wigs prior to 1970, and thus added to "the weight of previously amassed exculpatory evidence". His motion for DNA testing upon these fibers was transferred from the Fourth Circuit Court of Appeals to the district court. MacDonald's lawyers were also given the right to pursue DNA tests on limited hair and blood evidence on October 17, 1997.[181] This testing began in December 2000, with MacDonald's lawyers hoping the results would tie Stoeckley and her then-boyfriend, Gregory Mitchell, to the crime scene.[182][183]

On March 10, 2006, the Armed Forces DNA Identification Laboratory announced that the results of this DNA testing revealed that the DNA of neither Stoeckley nor Mitchell matched that upon any of the exhibits tested. Furthermore, although a single hair found within Colette's left palm was also cited by MacDonald as belonging to one of the alleged intruders, this testing also revealed the hair to have come from his own body.[184] This hair was also a precise match with others recovered from the bedspread within the master bedroom and upon the top sheet of Kristen's bed. A hair found in Colette's right palm was also determined to be her own. Three hairs, one from the bed sheet, one found in Colette's body outline in the area of her legs, and a single hair measuring one-fifth of an inch found beneath Kristen's fingernail did not match the DNA profile of any MacDonald family member or known suspect.[185]

In September 2012, the district court conducted a formal evidentiary hearing regarding DNA evidence and statements relating to key witnesses who offered testimony indicating MacDonald's innocence. On July 24, 2014, the district court rejected these claims in their entirety and re-affirmed MacDonald's conviction on all counts. Reportedly, MacDonald was disappointed, but not surprised, with this ruling.[186][187] He presented a motion to alter or amend this judgment to the district court, although this was denied in November 2014. He then appealed the denial of this motion to the Fourth Circuit Court of Appeals.[188] On December 21, 2018, the United States Court of Appeals for the Fourth Circuit affirmed the district court's ruling.[189]

In April 2021, MacDonald was denied a request for compassionate release upon the grounds of his ailing health,[190] with Judge Terrence Boyle citing the compassionate release law applies only to individuals whose crimes occurred on or after November 1, 1987.[191] A further appeal against this ruling was dismissed by the United States Court of Appeals for the Fourth Circuit on September 16, 2021.[192]

Later confession of Helena Stoeckley

[edit]Shortly after MacDonald's initial release from prison in August 1980, his supporters hired a retired FBI Special Agent and private investigator named Ted Gunderson to assist in overturning his conviction. Gunderson contacted Helena Stoeckley, who on this occasion confessed that she and five members of what she described as a "drug cult" had developed a deep grudge against MacDonald as he had "refused to treat heroin- and opium-addicted" patients. Accordingly, she and other members of this group had plotted revenge against MacDonald, intending specifically to murder his family but leave him alive.[n 29]

According to Stoeckley, she had telephoned the MacDonald residence late in the evening of February 16 to determine all members of the family were present in the house. Colette had answered and stated a babysitter would be there in the early evening but that after she had left, all the family would be present and alone. The group had then "dropped mescaline" before driving to the MacDonald residence. She and four others had entered the house and confronted MacDonald, intent on him signing a Dexedrine prescription, although the situation quickly deteriorated, with MacDonald attempting to fight his attackers before quickly lapsing into unconsciousness. Stoeckley alleged she then ran into the master bedroom to "find 'Death to All Pigs' or something like that" scrawled on the headboard and two of her friends bludgeoning Colette on the bed as her child lay asleep next to her. Stoeckley was adamant she had worn a beige, floppy hat on the evening in question.[33]

Stoeckley had submitted to a polygraph test in April 1971, with the military examiner stating: "It is concluded that Miss Stoeckley is convinced in her mind that she knows the identity of those person(s) who killed Colette, Kimberley, and Christine MacDonald. It is further concluded that Miss Stoeckley is convinced in her mind that she was physically present when the three members of the MacDonald family were killed. No abnormal physiological responses were noted in the polygraph tracings: however, due to Miss Stoeckley's admitted confused state of mind and her excessive drug use during and immediately following the homicides in question, a conclusion cannot be reached as to whether she, in fact, knows who perpetrated the homicides or whether she, in fact, was present at the scene of the murders."[194]

On April 16, 2007, MacDonald's attorneys filed an affidavit on behalf of Stoeckley's mother, Helena Teresa Stoeckley, who stated that her daughter had twice confessed to her that she was present in the MacDonald house on the evening of the murders and that her daughter was afraid of the prosecutors.[n 30] MacDonald requested to expand his then-outstanding appeal to include this affidavit alongside all the evidence amassed at trial, the developments which he claimed had been subsequently discovered (including the 2006 results of DNA testing), and the statements of individuals to whom Stoeckley had made these confessions. This appeal also alleged that the trial statements of prosecutor James Blackburn should be considered unreliable as he had been convicted of fraud, forgery, and embezzlement, and subsequently disbarred in 1993.

MacDonald's motions regarding the DNA results and the affidavit of Stoeckley's mother were denied. The denial of these two motions was based on jurisdictional issues, specifically that MacDonald had not obtained the required pre-filing authorization from the Circuit Court for these motions to the district court.[196] Nonetheless, the Fourth Circuit Court of Appeals granted MacDonald's motion for a successive habeas petition and remanded the matter back to the District Court Eastern Division.[197]

Britt affidavit

[edit]On January 12, 2006, MacDonald was granted leave to file a further appeal based upon a November 2005 affidavit of retired Deputy United States Marshal Jim Britt, who had served in this role during the trial. Britt stated that he had overheard Helena Stoeckley admit to prosecutor James Blackburn she had actually been present at the MacDonald house at the time of the murders and that Blackburn had threatened her with prosecution if she testified as a defense witness admitting this claim.[198] (Stoeckley had earlier met with the defense counsel prior to this alleged meeting with Blackburn, and informed them she had no memory of her whereabouts on the night in question.)[199]

In November 2008, Judge James Carroll Fox denied this appeal. This denial was based on the merits of the claim, specifically that, as Stoeckley had made many contradictory statements regarding her participation, or lack thereof, in the murders, her claims were unreliable. In addition, MacDonald's claim that Stoeckley had been expected to testify in a manner favorable to him at trial until she had been threatened by Blackburn is contradicted by the official trial records.[197]

Subsequent to this November 2008 decision, a government motion to modify the decision to negate Britt's claims was denied. Included within the motion was jail documentation establishing that Stoeckley was originally confined to the jail in Pickens, South Carolina, not Greenville, South Carolina, as Britt had claimed. Also included were custody commitment and release forms indicating that, although Britt and fellow Deputy United States Marshal Geraldine Holden had escorted Stoeckley into the Raleigh courthouse on August 16, 1979, agents other than Britt and Holden had actually transported Stoeckley to the 1979 trial.[199] MacDonald appealed the district court's denial of his claim to the Fourth Circuit Court of Appeals. In 2011, the Court of Appeals reversed this decision, remanding MacDonald's claims back to the district court for further consideration.[200]

MacDonald faced several legal obstacles in his efforts to incorporate a motion relating to the earlier results of DNA testing of hair and fiber evidence recovered from 544 Castle Drive into his motion regarding the claims made in Britt's affidavit, with the court stating he must obtain a pre-authorization for what should be a separate motion filed in relation to the results of the DNA testing. On April 19, 2011, the United States Court of Appeals granted a pre-filing authorization relating to his DNA claims, reversing the decision of the district court, and remanding his appeals for further proceedings.[200]

An evidentiary hearing relating to the claims within the Britt affidavit, the hair and fiber evidence, and further testimony pertaining to Stoeckley's verbal confessions, was held in September 2012.[186][201] However, in July 2014, Judge Fox ruled against MacDonald's appeal, upholding his convictions.[187]

Fatal Vision

[edit]In June 1979, MacDonald invited author Joe McGinniss to write a book about his case.[108] Initially unsure of MacDonald's guilt or innocence,[202] McGinniss agreed to his request, and was given full access to MacDonald and his defense team during the upcoming trial.[203]